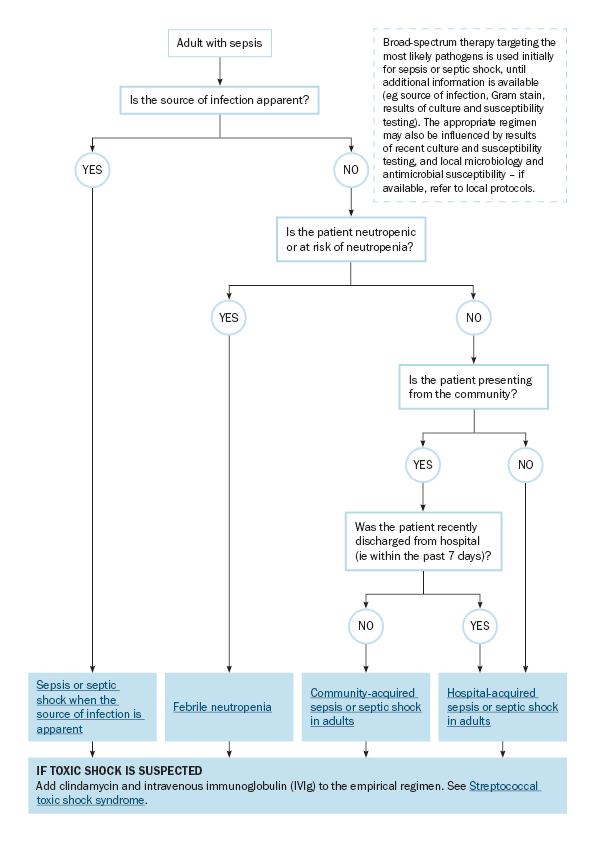

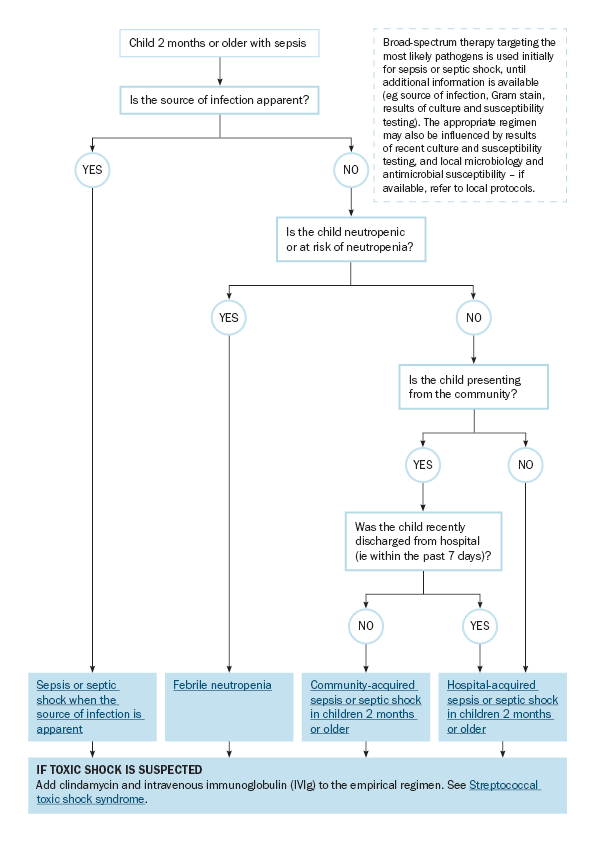

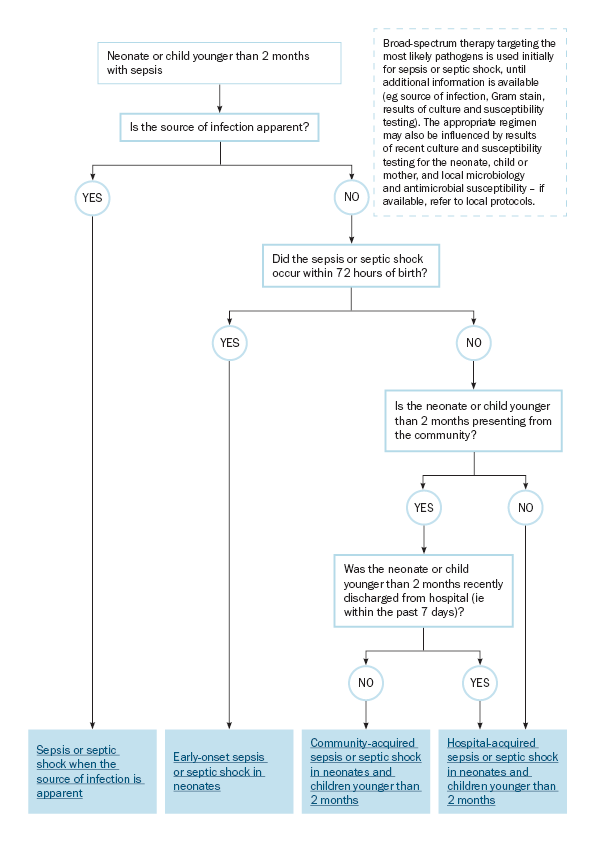

Choice of empirical antibiotic regimen for sepsis or septic shock of unknown source

Broad-spectrum therapy targeting the most likely pathogens is used initially for sepsis or septic shock, until additional information is available (eg source of infection, Gram stain, results of culture and susceptibility testing).

To find the right topic for sepsis or septic shock management when the source of infection is unknown or not apparent, use:

- Choice of empirical antibiotic regimen for sepsis or septic shock in adults for adults

- Choice of empirical antibiotic regimen for sepsis or septic shock in children 2 months or older for children 2 months or older, and

- Choice of empirical antibiotic regimen for sepsis or septic shock in neonates and children younger than 2 months for neonates and children younger than 2 months.

The choice of empirical regimen for sepsis or septic shock of unknown source is influenced by:

- the patient’s age – these guidelines include empirical regimens for neonates and infants younger than 2 months, children 2 months or older, and adults; the common pathogens causing sepsis or septic shock are different for each of these age groups

- whether the infection was acquired in the community or in hospital, or is associated with healthcare contact or overseas travel

- adults with community-acquired sepsis or septic shock of unknown source at presentation commonly have a final diagnosis of urinary tract infection, respiratory infection or primary bacteraemia. A range of pathogens may be involved including Escherichia coli, beta-haemolytic streptococci (Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus agalactiae [group B streptococcus], Streptococcus dysgalactiae), Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis. Infection with drug-resistant organisms (eg methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA], multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) is more common if the infection was acquired in hospital, or is associated with healthcare contact (eg outpatient dialysis or chemotherapy) or overseas travel. Furthermore, organisms that are rare in community-acquired sepsis (eg Candida species) may cause hospital-acquired or healthcare-associated infections.

- in children, important organisms causing community-acquired sepsis include S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, S. pyogenes and N. meningitidis, as well as E. coli associated with urinary tract infections. Just as in adults, other organisms are important causes of hospital-acquired bacteraemia and sepsis in children.

- in neonates and infants younger than 2 months, sepsis may be caused by S. agalactiae (group B streptococcus), herpes simplex virus (HSV), Listeria monocytogenes and E. coli.

- results of recent culture and susceptibility testing (relevant to the presentation). If these results suggest that likely pathogens are not susceptible to the empirical regimen, modified regimens are needed – seek expert advice

- whether infection with multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria is likely – alternative regimens are recommended throughout these guidelines

- whether infection with MRSA is likely – alternative regimens are recommended throughout these guidelines

- whether local microbiology and antimicrobial susceptibility is known; this is particularly important for infections acquired from healthcare contact, in hospital or overseas – refer to local or jurisdictional protocols and seek expert advice

- whether the patient has neutropenia or immune compromise. Patients with neutropenia are at increased risk of infection with P. aeruginosa and invasive fungal disease – see Febrile neutropenia for antibiotic choice. For patients with immune compromise but not neutropenia, the empirical antibiotic regimens in this topic may be appropriate; however, evaluate the appropriateness of the empirical regimen based on the patient’s susceptibility to infection, the underlying disease and comorbidities, and other patient factors

- whether toxic shock syndrome is suspected – clindamycin and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) should be added to the empirical regimen (see Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome for clinical presentation, and clindamycin and IVIg dosing). In children, paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome (PIMS-TS) can present similarly to toxic shock syndrome – seek expert advice and consider early referral to a paediatric hospital with intensive care facilities.