History and examination in fatigue

Listen carefully and take a detailed clinical history when evaluating patients who present with fatigueHamilton, 2010Murtagh, 2018. Understanding the patient’s symptoms, their usual level of physical activity, and what they mean by ‘fatigue’ can assist with diagnosis. Establishing a baseline can also aid evaluation of progress or response to treatment or supportive strategies.

Start with open questions to allow the patient to describe in their own words what they are experiencing, then ask more specific questions—for example:

- Could you explain to me exactly what you mean by [patient’s words]?

- What is your usual level of physical activity?

- What is the most strenuous thing you’ve done in the last week? How did you feel afterwards?

- How does the fatigue (and/or other terms used by the patient to describe the symptom) affect your daily life (eg ability to perform at work, ability to complete your usual daily tasks)?

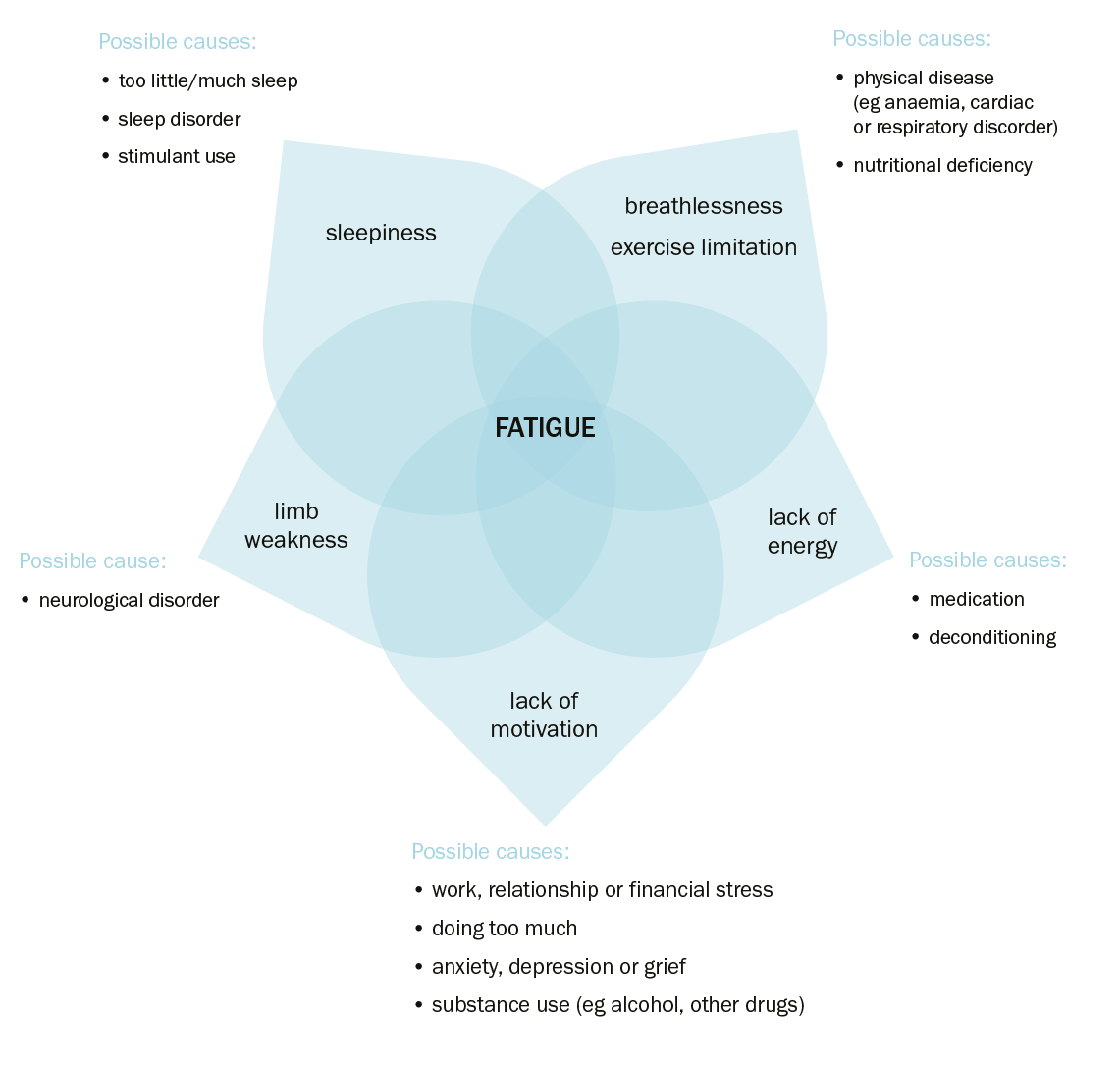

[NB1]

NB1: The lists of diagnoses are not exhaustive.

Other important aspects of a thorough fatigue history includeMurtagh, 2018:

- mode of onset (eg sudden, gradual, following acute illness)

- character (including severity, duration, progress over time, how the fatigue responds to exertion and rest)

- exacerbating and relieving factors

- associated symptoms

- impact on function (eg physical, mental, social, activities of daily living)

- psychological factors—patient fears, concerns (eg cancer fears if there is a family history) and goals

- mental health assessment (see Assessing a person with anxiety, Assessing a person with depressive symptoms and Rating scales for depressive symptoms)

- environmental factors (eg occupation, stressors related to work or relationships)

- behavioural factors (eg dietary; exercise, sleep and social practices; substance use [eg alcohol and other drugs])

- medication review (including complementary and over-the-counter medicines; see list below of medications commonly associated with fatigue)

- other medical conditions (see Conditions commonly associated with fatigue).

Medications that frequently cause or contribute to fatigue includeMaisel, 2021Murtagh, 2018:

- antiemetic drugs (eg domperidone, metoclopramide)Athavale, 2020

- antiepileptic drugs (eg sodium valproate, carbamazepine)Nadkarni, 2005

- sedating antihistamines (eg dexchlorpheniramine, promethazine)Randall, 2018

- psychotropic drugs (eg quetiapine, olanzapine)Keks, 2019

- cardiovascular drugs (eg beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors).

Targeted examination of patients with fatigue should be guided by the history, but also be sufficiently thorough to satisfy the patient and the doctor’s concerns about serious underlying diseaseHamilton, 2010Murtagh, 2018. Consider the patient’s overall health status; watch how they walk into the room, check their body weight and look particularly for pallor, organomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Assess cardiovascular status (eg congestive heart failure symptoms, murmurs). In children and adolescents, consider undiagnosed congenital heart disease. Empathic listening and physical examination are an important part of the evaluation of a patient with fatigue; even if nothing abnormal is found, patients often find clinical examination reassuring.

Red flags that raise the suspicion of serious underlying diseases are outlined in Red flags for serious underlying disease in patients with fatigue.

Look for red flagsMurtagh, 2018National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE), [2011] that may indicate serious underlying disease and warrant investigation. For example:

- recent onset of fatigue in a previously well, older patient

- unintentional weight loss

- abnormal bleeding

- shortness of breath

- unexplained lymphadenopathy

- fever

- recent onset or worsening of fatigue in a patient with an underlying chronic condition.