Diagnosing multiple sclerosis

|

More specific symptoms of multiple sclerosis that often reflect disease activity [NB3] |

Less specific symptoms of multiple sclerosis [NB4] |

|---|---|

|

acute painful loss of vision in one eye (optic neuritis) limb weakness and numbness that can occur with or without bladder/bowel dysfunction, sometimes with acute pain (transverse myelitis) ataxia, facial numbness or diplopia (brainstem syndrome) first episode of trigeminal neuralgia (rare) hemiplegia (hemisphere syndromes; rare) new onset of Lhermitte phenomenon [NB5] tonic spasms (rare, more likely to be neuromyelitis optica) |

cognitive dysfunction recurrence of Lhermitte phenomenon [NB5] |

|

Note:

NB1: The course of multiple sclerosis varies among patients, but the prognosis may be poorer in patients with:

NB2: Symptoms that are rare in multiple sclerosis and should prompt consideration of different diagnoses include dysphasia, new headaches, hemiplegia, movement disorders and seizures. NB3: Likely to need corticosteroid treatment NB4: Likely to need symptomatic treatment NB5: The Lhermitte phenomenon is sudden transient electric-like shocks that spread down the body when the patient flexes the head forward. | |

The diagnosis of MS is based on the presence of typical lesions throughout the CNS, shown clinically and on MRI (see Typical demyelinating lesions in multiple sclerosis), with new lesions occurring over time. Using accepted criteria, MS can be diagnosed after a single clinical event if the MRI shows lesions of different ages.

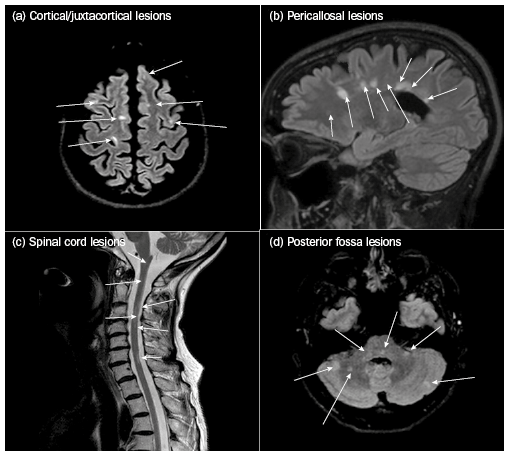

Axial brain, sagittal brain, sagittal spine and axial cerebellar sections from fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) magnetic resonance imaging.

(a) Typical cortical lesions have a curvilinear, juxtacortical distribution involving U-fibres.

(b) Pericallosal / periventricular lesions abut the ependymal surface and radiate linearly towards the brain surface.

(c) Spinal cord lesions are short segment (fewer than three vertebral spaces), usually involve part of the spinal cord and can traverse grey and white matter.

(d) Posterior fossa lesions are ovoid or circular and involve the cerebellum, pons, medulla and midbrain.

Other tests that can be useful when diagnosing MS are:

- cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis—this shows the typical inflammatory process (oligoclonal bands in the CSF without matching bands in the serum)

- evoked potential measurement—this shows electrophysiological evidence of a demyelinating lesion in the spinal cord (somatosensory evoked potential [SSEP]), optic nerve (visual evoked potential [VEP]) or (rarely) the brainstem (brainstem auditory evoked response [BAER]).

Some patients have a single demyelinating event without evidence of changes over time (ie no new clinical events and/or new lesions on MRI)—this is called a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), and patients must be monitored in case MS develops. If the initial MRI shows two or more white matter lesions, the patient has about an 80% risk of developing MS—if the MRI is normal, the risk falls to about 11%.

Before confirming a diagnosis of MS, the expert excludes other neuroinflammatory diseases (eg acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, neuromyelitis optica [NMO] spectrum disorders, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus).

If the patient has a progressive presentation, as well as excluding the differential diagnoses above, the expert needs to consider other conditions that mimic MS (eg vitamin B12 deficiency, spinal cord masses and fistulas, genetic syndromes [eg hereditary spastic paraparesis]).

Patients with NMO spectrum disorders (neuromyelitis optica [Devic disease] and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein [MOG] NMO spectrum disorders) can present with:

- symptoms of optic neuritis that is more often bilateral or sequential than in MS

- transverse myelitis, usually with long cord lesions

- intractable hiccups or vomiting, due to a brainstem lesion.

A simple blood test (aquaporin-4 antibodies for NMO spectrum disorders, or MOG antibodies for MOG NMO spectrum disorders) diagnoses these conditions, which are treated differently from MS—patients with NMO spectrum disorders may deteriorate if given MS drug therapy. For treatment, refer for expert advice.