Overview of pharmacological management of acute pain

This topic describes the use of pharmacotherapy for acute pain and should be read in conjunction with the General principles of acute pain management topic, which defines the role of pharmacotherapy in the multidimensional management of acute pain. The management approach described in this topic is not appropriate in all circumstances; if the goals of care are palliative, manage acute pain according to the principles in Principles of managing pain in palliative care. For time-limited acute pain associated with a procedure, see Procedural sedation and analgesia.

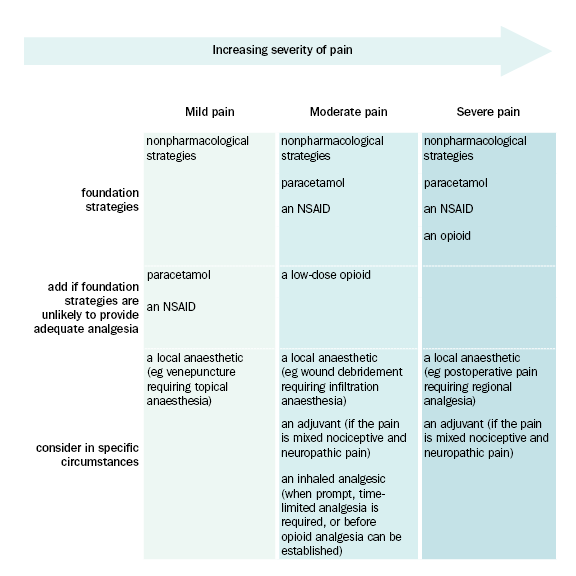

Start pharmacotherapy for acute pain if nonpharmacological interventions are unlikely to adequately relieve pain. A combination of analgesics is often used to produce synergistic effects; see Multimodal analgesia for acute pain.

[NB1]

NSAID: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

NB1: This figure describes management strategies for nociceptive pain, or mixed nociceptive and neuropathic pain.

NB2: Pain severity occurs on a spectrum between no pain and worst pain imaginable. To help practitioners choose the treatment regimen that best matches the pain experienced by their patient, especially when opioids are indicated, these guidelines include specific definitions of mild, moderate and severe pain. However, there are no universal definitions of mild, moderate and severe pain, and other publications may define these categories differently.

- Mild, acute nociceptive pain

- Moderate, acute nociceptive pain

- Severe, acute nociceptive pain

- Acute neuropathic pain.

|

Drug or drug class |

Role of analgesic |

|---|---|

|

first-line analgesic in adults and children for acute nociceptive pain because of its favourable adverse effect profile used alone, or as a component of multimodal analgesia for nociceptive pain | |

|

used alone, or as a component of multimodal analgesia for nociceptive pain useful for pain with an inflammatory component use may be contraindicated, or the choice of NSAID limited, because of potential adverse effects | |

|

inhaled analgesics (eg methoxyflurane, nitrous oxide) |

used for trauma-related pain before arrival at hospital used for short-term pain relief not used for ongoing treatment of pain |

|

local anaesthetics (eg lidocaine) |

used for specific acute pain presentations (eg local anaesthesia for wound repair, regional analgesia for postoperative pain, topical treatment for oral mucositis) |

|

used as a component of multimodal analgesia for moderate or severe nociceptive pain the use of high or frequent doses, or parenteral or intranasal administration is restricted to use in settings that meet the monitoring and staffing requirements for opioid administration tramadol or tapentadol are unlikely to provide adequate relief of severe pain because their dosing is limited by effects at other receptors; tramadol and tapentadol are less likely to cause excessive sedation and opioid-induced ventilatory impairment than other commonly used opioids | |

|

adjuvants (eg gabapentinoids) |

used for acute neuropathic pain may reduce central sensitisation processes following surgery or trauma gabapentinoids are opioid-sparing |

Note:

NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs NB1: Analgesics should be used in combination with nonpharmacological approaches. | |

The most appropriate route of administration depends on whether the patient can take medicines by mouth and the urgency of analgesia (eg intravenous administration may be preferred if prompt analgesia is required for severe pain; intranasal administration may be used in an anxious child for severe pain while establishing intravenous access). Most children, and even a few adolescents, are unable to swallow tablets no matter how much coaching they have. Oral drug formulation significantly affects drug choice in children; dispersible tablets or liquid formulations are preferred.

Analgesic doses for children should be based on the child’s weight. Take care calculating doses to choose the appropriate weight (ie actual or ideal body weight) and ensure accuracy; dose (mg) and volume (mL) mix-ups have caused 10-fold overdoses in young children.

- For children who are underweight or of healthy weight, use actual body weight to calculate the dose.

- For children who are overweight or obese (ie more than 20% heavier than their ideal body weight), use ideal body weight to calculate the dose—using the child’s actual body weight to calculate the dose will result in an excessive dose. Estimate the child’s ideal body weight using the corresponding weight for the height percentile on the growth chart, see the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.

Regularly review the efficacy of analgesics—see here for a guide to assessment. If adequate analgesia is not achieved within the expected timeframe or with expected doses, consider if:

- the pain is not responsive to the analgesic regimen (eg if the pain is not opioid responsive, the patient may experience ongoing severe pain despite becoming sedated)

- the route of administration is inappropriate (eg trauma patients may have impaired oral absorption and require administration by an alternate route)

- there are other factors contributing to the pain that have not been addressed (eg psychosocial factors, a surgical complication, a new pathology).

When starting an analgesic for acute pain, always have a tapering and stopping plan; analgesics should not be continued after the acute illness or injury has resolved.