Principles of care for a patient with acute behavioural disturbance

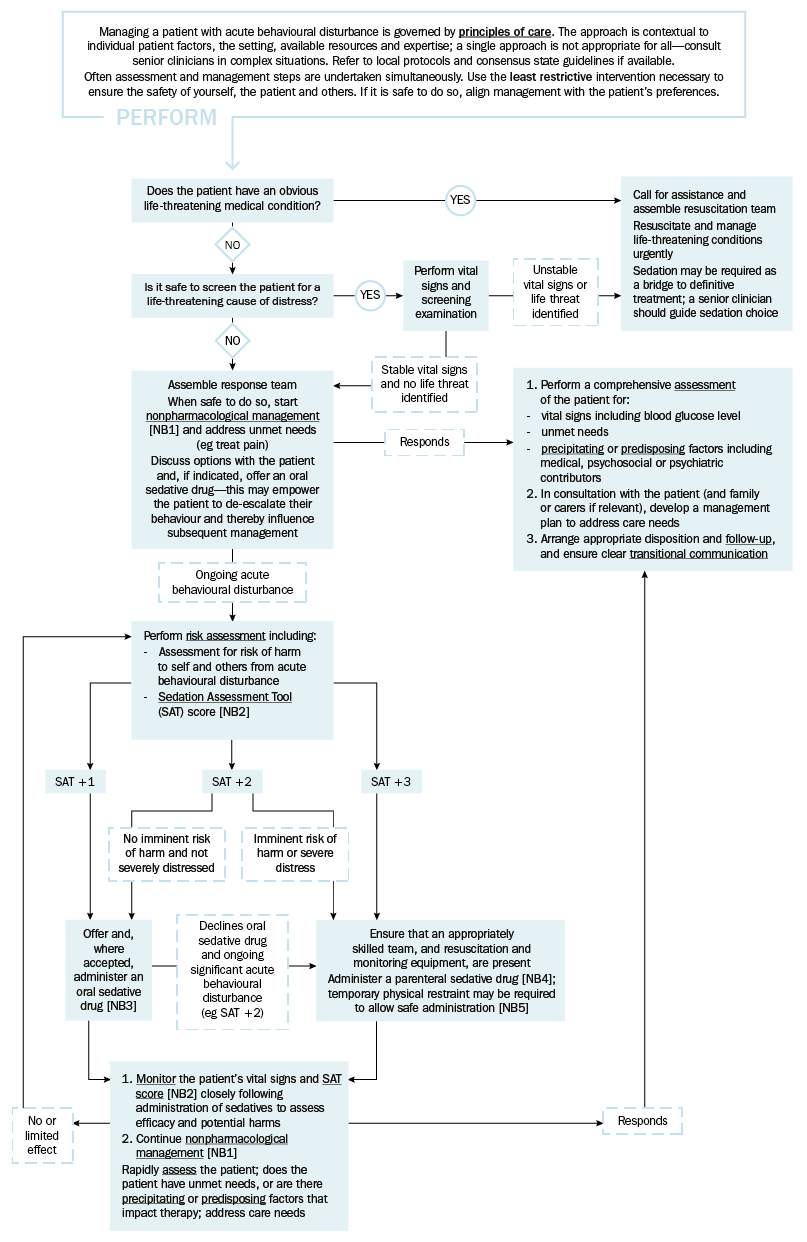

The approach to assessing and managing a patient with acute behavioural disturbance varies according to individual patient factors, the risk of significant harm to self or others, and the setting. The principles of care must uphold the human rights of the person as well as prevent harm—see Principles of care for a patient with acute behavioural disturbance for principles of care for a patient with acute behavioural disturbance.

- Use a multidisciplinary approach, with nonpharmacological management techniques (eg environmental management [adaption], verbal de-escalation and psychological intervention, risk mitigation) and, if indicated, pharmacological management.

- Use interventions proportionate (ie not excessive) to the severity of risk posed by the acute disturbance—always consider the least restrictive intervention available initially; only use restrictive practices as a last resort.

- Individualise management to ensure the interventions are contextualised for patient-specific factors (eg clinical, risk, patient’s preferences). Consider a modified approach for specific populations (eg children, older people, drug and alcohol users).

- Monitor the patient’s physical and psychiatric health, risk of harm to self or others, engagement level, and response to management.

- If the patient has differentiated predisposing or precipitating factors for the acute behavioural disturbance, prioritise and optimise treatment of the underlying factors.

- If the patient has undifferentiated behavioural disturbance, establish any factors that may be contributing to the disturbance when it is safe to perform a comprehensive assessment.

Managing a patient with acute behavioural disturbance is a detailed flowchart for managing a patient with acute behavioural disturbance.

SAT = sedation assessment tool

NB1: Nonpharmacological management techniques include environmental management (adaption), verbal de-escalation and psychological intervention and risk mitigation. For children, older people, and people with developmental disability or cognitive impairment, the situation can often be de-escalated with nonpharmacological management techniques.

NB2: Consider the SAT score in the context of the patient’s baseline function and communication style (eg loud outbursts may be usual for individuals with dementia or a developmental disability). Individualise the target SAT score based on patient factors (eg response to nonpharmacological interventions, whether the patient needs to be sedated for investigations) and the ability to maintain patient and staff safety.

NB3: If an oral sedative drug is required, see the regimens for adults, older people and children.

NB4: If a parenteral sedative drug is required, see the regimens for adults, older people and children.

NB5: Restraint must be proportionate to the risk of harm and only be used for the minimum duration that ensures the safety of the person and others. Follow local protocols with appropriate governance and staff training. See physical restraint for detailed information.

NB6: Often multiple factors can precipitate an acute behavioural disturbance.

Any healthcare professional involved in managing patients with acute behavioural disturbance must be trained in the safe and effective delivery of both nonpharmacological management and pharmacological management. Best practice is supported by a standardised multidisciplinary approach with governance. If possible, refer to local protocols and consensus state guidelines, and seek expert advice to assist in managing difficult cases. Legal requirements for management of acute behavioural disturbance must also be met.

If the patient requires immediate intervention because of an imminent threat of harm to self or others, the principle of ‘duty of care’ may be used as a rationale for medical intervention without obtaining consent. If in doubt, consider the likely consequences of not intervening. Seek expert advice from a senior colleague whenever possible. Intervening without consent may be regarded as assault; however, many patients do not have the capacity to consent to treatment in these situations (eg children, people with developmental disability or cognitive impairment, alcohol- or drug-affected people). If it is safe to do so, discuss the patient’s distress and behaviour, and management options, with them and/or their carer, guardian or substitute decision maker. For more detailed information, see:

- Informed consent and shared decision making in people with a psychiatric disorder

- Consent, capacity and decision making for people with developmental disability.

Any form of restrictive practice (eg pharmacological management, physical or mechanical restraint) should only be used as a last resort, and reserved for patients whose behaviour poses an imminent risk of significant harm to self or others.

Restrictive practices are discouraged in all people, particularly children, older people, and people with developmental disability or cognitive impairment. If restrictive practices are required, they must be proportionate to the risk of harm, and be employed for the minimum duration that ensures the safety of the person and others; see here for more information.

Careful documentation of care for a person with acute behavioural disturbance is essential—at a minimum, record:

- the patient’s perspective on their presentation, and relevant collateral

- the rationale for any intervention

- clinical evidence of the patient’s capacity and whether consent was obtained

- if relevant, how the patient satisfies the criteria necessary to invoke involuntary treatment under the relevant legislation

- management strategies employed (including details of any restrictive practices) and whether adverse effects were experienced

- details of physical and mental state examination.