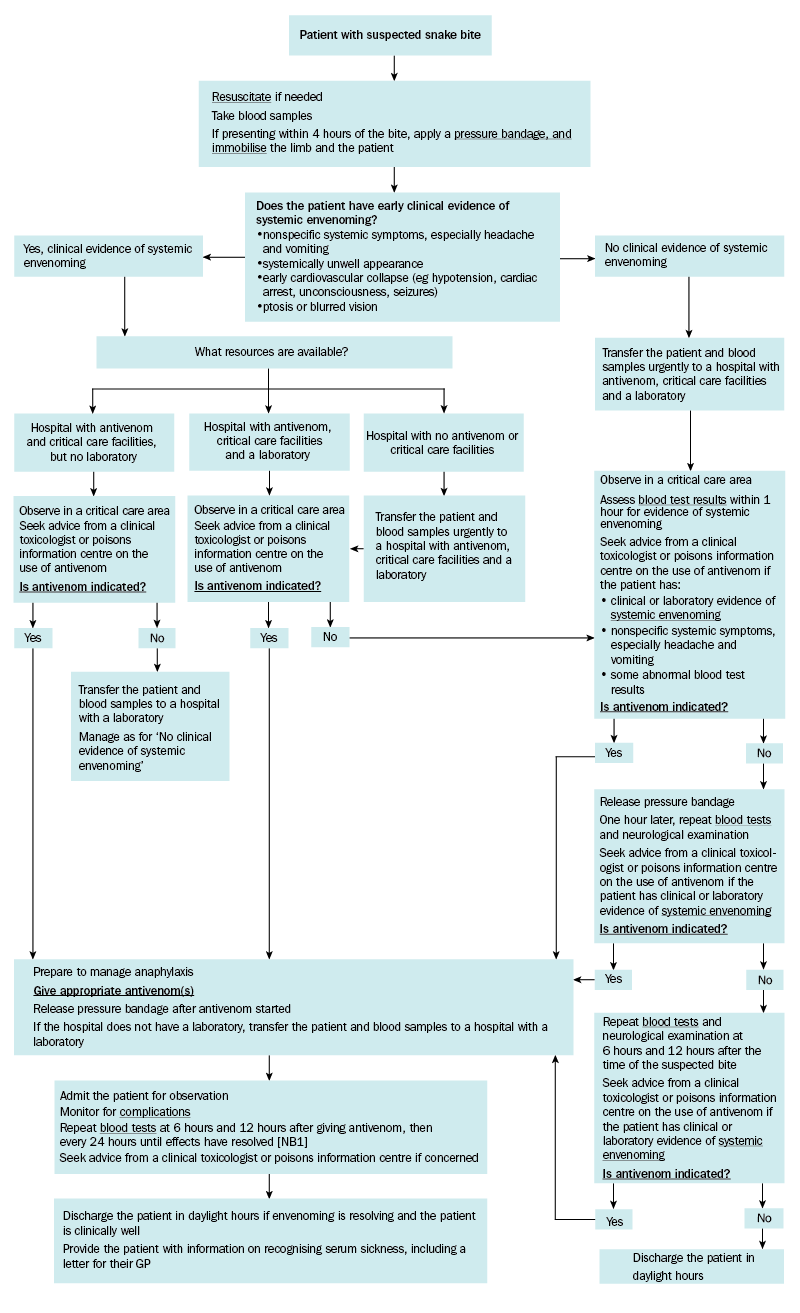

Treatment for snake bite: principles of hospital management

Manage all patients with suspected snake bite in a hospital that has all of the following:

- adequate antivenom

- a 24-hour onsite laboratory that can perform coagulation studies

- critical care facilities where antivenom can be safely administered and anaphylaxis can be treated.

If the hospital has adequate antivenom and critical care facilities, but no laboratory, antivenom can be given (if indicated) and the patient transferred to a hospital with a laboratory later.

The three critical steps in the management of a snake bite are to:

- determine if the patient has evidence of systemic envenoming (see Evidence of systemic envenoming from snake bite)

- if so, determine if antivenom is indicated

- if so, determine which snake group(s) are likely to be responsible for the bite, to guide the choice of antivenom(s).

For antivenom dosing, see here.

Take blood for key investigations. If the patient is going to be transferred to a different hospital, ensure the blood samples accompany the patient.

Even if the patient has no clinical evidence of systemic envenoming, do not remove the pressure bandage unless antivenom therapy has started, or laboratory assessment confirms there is no evidence of systemic envenoming.

For treatment of the major complications of snake bite, see here.

Most envenomed patients have multiple clinical or laboratory abnormalities suggestive of systemic envenoming.

Clinical evidence of systemic envenoming includes:

- neurotoxicity

- myotoxicity

- coagulopathy

- acute kidney injury

- nonspecific systemic symptoms: nausea, vomiting, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, sweating

- early cardiovascular collapse (eg hypotension, cardiac arrest, unconsciousness, seizures)

- significant local bite site effects.

Laboratory evidence of systemic envenoming includes:

- INR more than 1.2

- prolonged APTT

- low or undetectable fibrinogen concentration

- raised quantitative D-dimer (more than 2.5 mg/L)Isbister 2022

- serum creatine kinase concentration more than 1000 units/L

- raised serum creatinine concentration

- evidence of thrombotic microangiopathy—thrombocytopenia, red cell fragments or spherocytes on blood film, raised serum lactate dehydrogenase concentration

- raised white cell count.

APTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; INR = international normalised ratio

NB1: Coagulopathy may not begin to improve until about 12 hours after the snake bite. Persistent coagulopathy is not an indication for additional antivenom. Seek advice if concerned.