General principles of the periprocedural use of warfarin

The large variety of possible surgical procedures and unique patient-related considerations mean that the periprocedural use of warfarin requires clinical judgement, specialist input and a consensus between the treating clinicians. Discuss the risks and expected benefits with the patient.

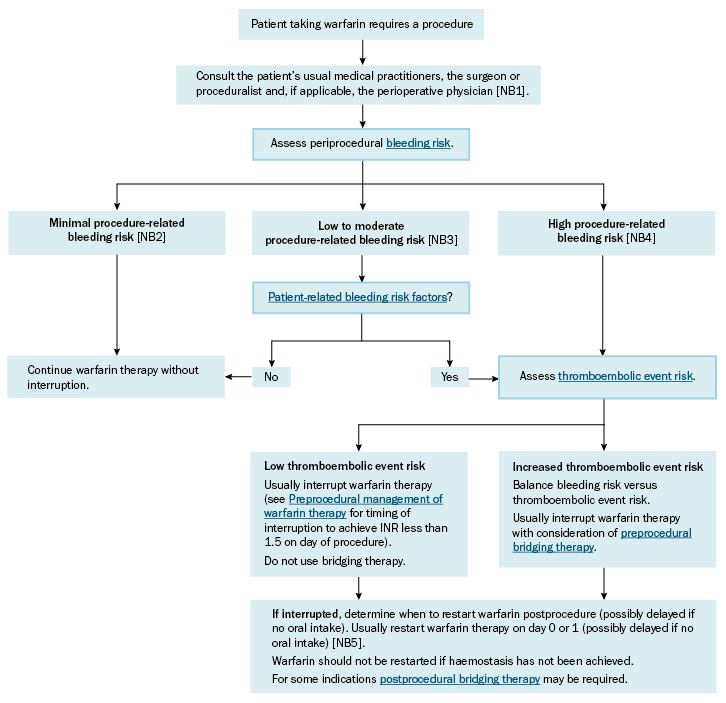

See Stepwise approach to periprocedural use of warfarin for a guide to deciding whether and when to interrupt warfarin therapy, whether to use bridging therapy before and/or after the procedure, and when to restart warfarin therapy if it is interrupted.

If patients taking warfarin require an emergency procedure, consider rapid reversal of warfarin therapy. For information on the reversal of warfarin, see Bleeding and overanticoagulation with warfarin.

If patients taking warfarin require an elective procedure, assess the periprocedural risk of bleeding and periprocedural risk of thromboembolic events to determine management. Some procedures with a minimal risk of bleeding may not require interruption of warfarin therapy. Interruption may be appropriate if the patient- or procedure-related bleeding risk is increased. Rapid reversal of anticoagulant therapy is usually not used for elective procedures; vitamin K1 may reverse warfarin for a considerable time, which delays therapeutic anticoagulation after the procedure1.

If interruption of warfarin therapy is required, bridging therapy (with subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin [LMWH] or intravenous unfractionated heparin [UFH]) is sometimes used before and/or after the procedure to reduce the thromboembolic event risk associated with warfarin interruption. However, warfarin has a prolonged duration of effect, so bridging therapy is often not required when warfarin is interrupted.

INR = international normalised ratio

NB1: The large variety of possible surgical procedures and unique patient-related considerations mean these decisions require clinical judgement, specialist input, and consensus between the treating clinicians. Discuss the risks and expected benefits with the patient.

NB2: Minimal-risk procedures are those with no clinically relevant risk of major bleeding (eg minor dental extractions, skin excisions of less than 1 cm, cataract procedures).

NB3: Low- to moderate-risk procedures are those with a possibility of major bleeding, but a low incidence (eg laparoscopic cholecystectomy).

NB4: High-risk procedures are those with a higher incidence of major bleeding, which include procedures that are invasive (eg bowel resection, major orthopaedic surgery) or involve highly vascular organs (eg kidney, liver, spleen), as well as procedures with a low incidence of bleeding but for which a minor bleed can cause significant morbidity or mortality (eg intracranial, spinal or cardiac surgery).

NB5: Day 0 is the day of the procedure; day 1 is the first day after the procedure.